Discovering Candomblé: Foundations in Afro Brazilian Religion

Before visiting Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, I was fascinated by traditional African spirituality and began learning about the Orishas and their rituals. Days before my trip, I experienced my first divination based on African cosmology, which was eye-opening.

Before visiting Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, I was fascinated by traditional African spirituality and began learning about the Orishas and their rituals. Days before my trip, I experienced my first divination based on African cosmology, which was eye-opening.

Upon arriving in Salvador, I observed traces of Ifa—the West African religion of the Yoruba people from modern-day Nigeria and Benin—in the dress, food, and public art, deepening my curiosity.

Over the years, I engaged in a variety of Ifa, Lucumi, Candomblé, Mosi, & Dagara readings, prayer rituals, spiritual baths, and head cleansing, all leading to the discovery of my Orisha. Most recently, my path has been guided by Candomblé Ketu practitioners, each experience expanded my cultural understanding and my journey of self discovery.

I am thankful that my travels through the Americas and West Africa coupled worthy my undying curiosity created openings and options for me to discover.

This post explores the historical, religious, and sociocultural context of Candomblé Ketu and its central role in Brazil’s broader Afro-Brazilian religious landscape.

What is Candomblé

Candomblé is an Afro-Brazilian religion that emerged in the 19th century, blending traditional West and Central African spiritual practices with elements of Roman Catholicism. It centers on the veneration of deities known as Orixás, each associated with specific natural elements and human endeavors.

Candomblé is an Afro-Brazilian religion that emerged in the 19th century, blending traditional West and Central African spiritual practices with elements of Roman Catholicism. It centers on the veneration of deities known as Orixás, each associated with specific natural elements and human endeavors.

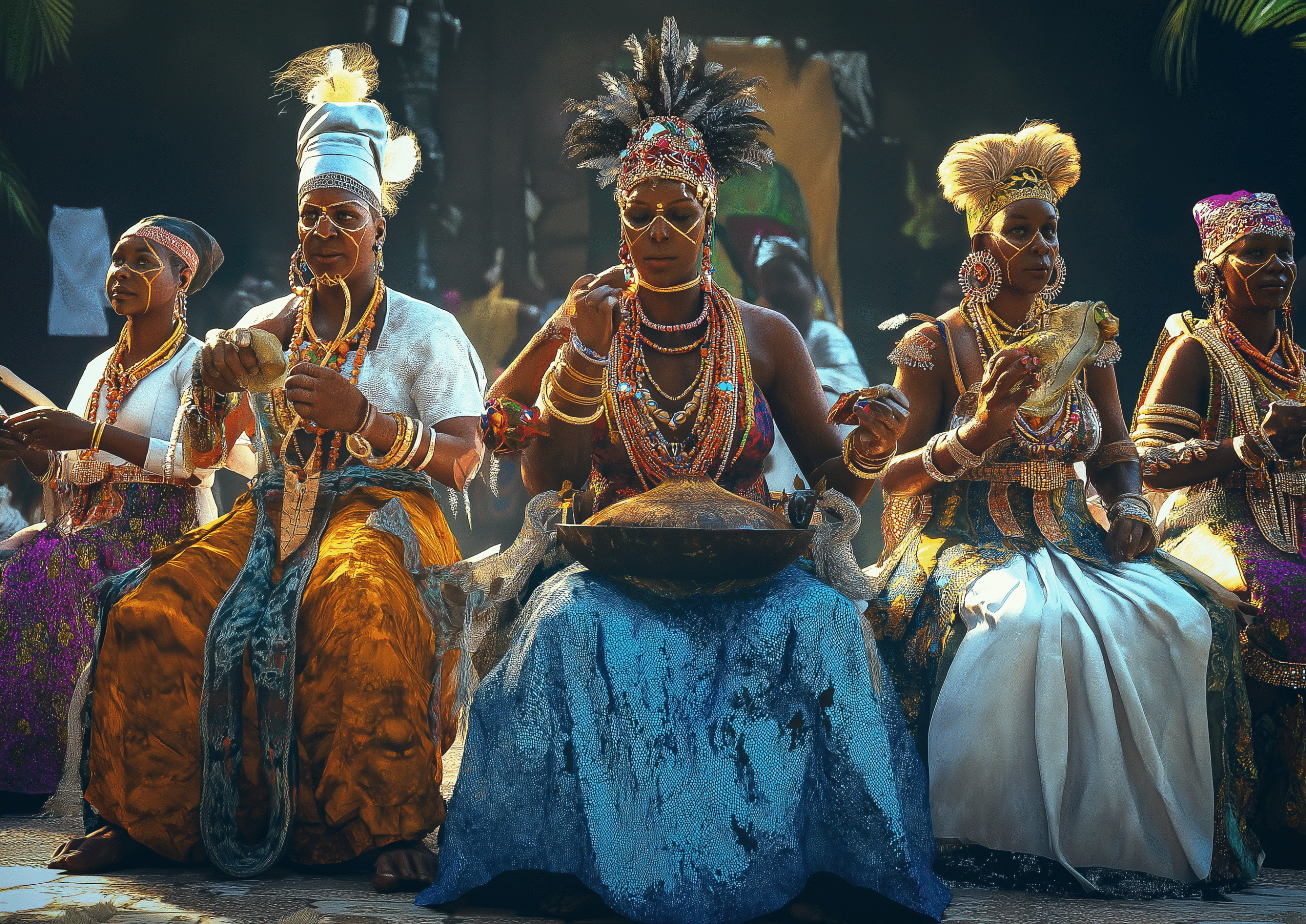

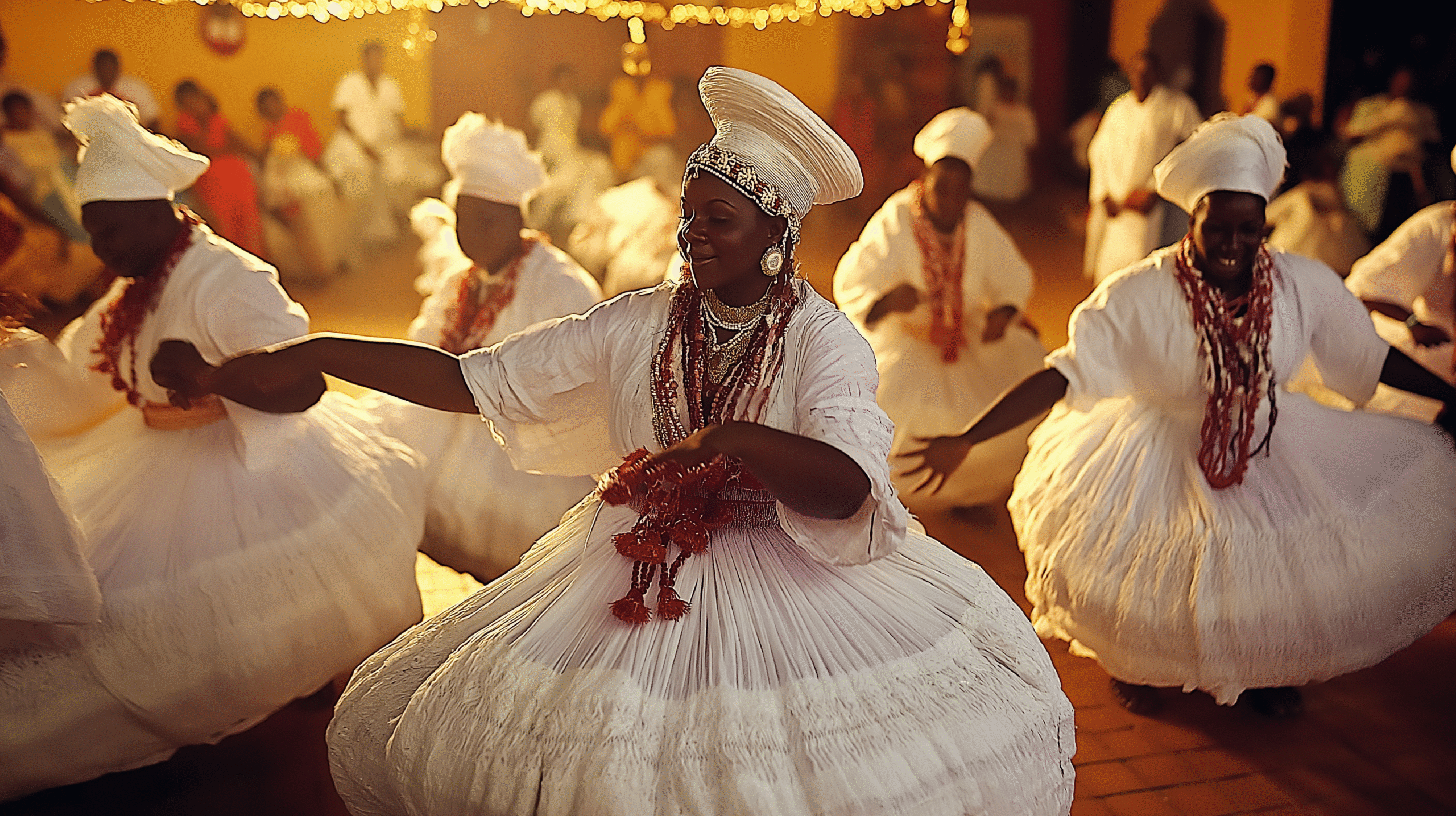

Practitioners engage in rituals involving drumming, singing, and dance to communicate with these deities, seeking guidance and blessings. The religion is organized into autonomous terreiros (temples), each led by a mãe de santo (priestess) or pai de santo (priest).

Within Candomblé, there are several branches, known as nações (nations), each reflecting the traditions of different African ethnic groups:

- Ketu (Nagô): Originating from the Yoruba people, this is the largest and most influential nation in Brazil. It emphasizes the worship of the Orixás and maintains many traditional Yoruba practices.

- Jeje: Based on the traditions of the Fon people from the Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin), Jeje Candomblé incorporates elements of Vodun and is known for its distinct rituals and deities.

- Angola: Reflecting the spiritual practices of the Bantu peoples from Angola, this nation focuses on ancestral veneration and the worship of deities known as Inkices.

Each nation has its own unique rituals, deities, and cultural expressions, contributing to the rich diversity of Candomblé in Brazil.

The Significance of Ketu in Brazilian Candomblé

Ketu, also known as Queto, is the largest and most influential nation (nação) within Brazilian Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religion that synthesizes African traditions with Brazilian cultural elements. Its significance lies in its historical origins, theological framework, ritual practices, linguistic preservation, and sociopolitical impact.

Originating from the Yoruba-speaking regions of West Africa, particularly the Kingdom of Ketu in present-day Benin, Ketu Candomblé has profoundly shaped the religious and cultural landscape of Brazil, which offers a unique space for social organization and communal resilience.

Historical Context

The transatlantic slave trade forcibly brought millions of Africans to Brazil, among whom were the Yoruba people from the Kingdom of Ketu, a vassal state of the Oyo Empire in present-day Benin and Nigeria. These enslaved individuals carried with them rich religious traditions centered around the worship of deities known as Orixás. In Brazil, these traditions evolved into distinct religious practices, with Ketu Candomblé preserving many elements of the original Yoruba faith.

The Kingdom of Ketu was one of the most significant city-states within the Yoruba cultural sphere, possessing a distinct religious and political structure. Ketu’s military conflicts with Dahomey (Fon-speaking) and Oyo (Yoruba-speaking but politically dominant) led to increased slave exports from the region, which fueled the growth of Ketu-based religious traditions in Brazil.

The arrival of Ketu slaves in Brazil, particularly in Salvador (Bahia), Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, established a Yoruba-influenced religious system that, despite colonial oppression, maintained key theological and ritualistic elements.

Orixa Pantheon Foundations

At the core of Candomblé Ketu is the belief in a Supreme Being, Olodumare, who is the source of all creation. The Orixás are revered as intermediaries between humans and Olodumare, each governing specific natural elements and human endeavors. The pantheon of Orixás in Ketu Candomblé includes:

Iemanjá: Mother of the Orixás, goddess of the ocean, and protector of fishermen and families. She represents motherhood, nurture, and emotional depth.

Logun Edé: Embodies both Oxóssi and Oxum, balancing masculinity and femininity. He is a hunter and a ruler of waters, associated with beauty, agility, and intelligence.

Ewá: Orixá of divination, clairvoyance, and mystery. She governs intuition, chastity, and the hidden aspects of life.

Obá: Warrior Orixá associated with discipline, sacrifice, and loyalty. She is strong, protective, and misunderstood in many myths.

Iansã (Oyá): Fierce warrior goddess of winds, storms, and the dead. She is associated with transformation, intuition, and the ability to navigate life’s turbulence with courage. She also commands the Eguns (spirits of the dead).

Exu (Elegbara): Messenger of the Orixás and the guardian of crossroads, communication, and movement. He is seen as a trickster, balancing chaos and order, and plays a crucial role in rituals as the one who opens the spiritual paths. Despite being sometimes misunderstood, Exu is not an evil figure but rather an energetic force governing change and transformation.

Ogun: Warrior and blacksmith, associated with metal, war, technology, and progress. He is a fearless and strong Orixá who clears paths, protects soldiers, and governs work, especially jobs related to iron and tools.

Omolu/Obaluaiê: Omolu (elder) and Obaluaiê (younger) are associated with disease, healing, and transformation. They govern health, medicine, and the mysteries of life and death. They are powerful but often misunderstood, as they bring both suffering and its cure.

Oxumaré: The Orixá of rainbows, cycles, and continuity. He represents transformation, renewal, wealth, and movement. He is both male and female, embodying duality and balance.

Nanã Buruquê: The oldest of the female Orixás, associated with wisdom, the past, and the connection between life and death. She governs the mud, which is the origin of all life and the medium through which spirits transition.

Oxum: Goddess of freshwaters, beauty, wealth, and fertility. She governs love, intuition, and femininity. She is gentle yet strong, embodying the power of water to nourish and erode.

Oxóssi: The hunter, provider, and guardian of the forests. He is associated with abundance, wisdom, and the ability to track and attain goals. He is a solitary but generous Orixá, ensuring sustenance and protection.

Xangô: Orixá of thunder, justice, and fire. He represents power, leadership, and intelligence. He is a symbol of masculinity and fairness, ensuring that truth prevails and punishing dishonesty. He is also linked to fire and the stone that falls from the sky (lightning).

Organization and Structure

Terreiro – Ketu terreiros, which are sacred houses of worship serve as microcosms of Yoruba cosmology, structured around hierarchical priesthoods, ritual performance, and social organization. Led by a babalorixá (priest) or ialorixá (priestess), who oversee the religious community. These spaces also function as resistance institutions, preserving Yoruba epistemologies despite colonial and postcolonial marginalization.

Terreiro – Ketu terreiros, which are sacred houses of worship serve as microcosms of Yoruba cosmology, structured around hierarchical priesthoods, ritual performance, and social organization. Led by a babalorixá (priest) or ialorixá (priestess), who oversee the religious community. These spaces also function as resistance institutions, preserving Yoruba epistemologies despite colonial and postcolonial marginalization.

Divided into distinct spaces, terreiros, include the barracão (main ritual hall), peji (altar room), and private quarters for initiates, each playing a crucial role in religious practices.

From a community perspective, terreiros have been used as centers for Black empowerment and sites of political mobilization against religious intolerance, particularly from evangelical fundamentalists.

Rites of Passage and Initiation – Essential for establishing a devotee’s spiritual connection with their Orixá and integrating them into the religious community. The initiation process, known as feito de santo, is a deep spiritual transformation that includes seclusion, ritual purification, and the learning of sacred songs, dances, and symbols.

During this period, the initiate undergoes a series of rituals to strengthen their bond with their patron Orixá, including receiving their orí (spiritual headwashing) and undergoing the borí (a ritual to harmonize their energy). The process also involves the shaving of the head, symbolizing rebirth, and the wearing of specific garments and beads that mark their new spiritual identity.

These rites ensure the continuity of ancestral wisdom, strengthen communal bonds, and affirm the devotee’s lifelong commitment to the faith. Ultimately, initiation is both a personal transformation and a reaffirmation of the sacred traditions of Candomblé Ketu.

Drumming, Dance, and Oriki – Core elements in Candomblé Ketu, serving as dynamic conduits to connect practitioners with the divine. The rhythmic beating of atabaques (drum) and expressive dance facilitate spirit possession and help invoke the presence of the Orixás during ceremonies.

Drumming, Dance, and Oriki – Core elements in Candomblé Ketu, serving as dynamic conduits to connect practitioners with the divine. The rhythmic beating of atabaques (drum) and expressive dance facilitate spirit possession and help invoke the presence of the Orixás during ceremonies.

The important of dance is central to expressing the identity of each Orixa who all have their own individual dances reenacted by devotees. Along with dancing, singing known as Oriki is performed to aid in Orixa manifestation creating an intimate balance of call and response all commanded by beating atabaques.

Oriki, a sacred praise poetry—recalls ancestral traditions and extols the virtues of each Orixá, deepening devotees’ spiritual engagement and reinforcing communal identity.

Together, these practices create a vibrant, multi-sensory ritual environment that nurtures a profound and transformative connection to the sacred.

Cultural Religious Resistance – One of the most debated aspects of Ketu’s significance is its historical engagement with religious syncretism. During the colonial period, Orixás were often syncretized with Catholic saints to avoid persecution. Contemporary trends in Candomblé Ketu reflect a re-Africanization movement, aiming to remove Catholic influences and reassert Yoruba purity.

Examples of traditional syncretism include:

- Oxalá = Jesus Christ

- Iemanjá = Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes

- Xangô = Saint Jerome

However, many modern Ketu practitioners reject this syncretism, emphasizing the importance of pure Yoruba cosmology.

Women in Leadership – Unlike Catholicism, Candomblé Ketu empowers female spiritual leaders (Mães de Santo), creating matriarchal structures that resist patriarchal domination.

Women play pivotal roles, particularly as leaders of many terreiros reflecting a matriarchal influence within the religion. Their responsibilities encompass ritual leadership, transmission of sacred knowledge, and maintenance of cosmic harmony. Additionally, women are primarily tasked with domestic duties within the ritual space, ensuring its upkeep and sanctity.

This blend of leadership and domestic roles underscores women’s centrality in preserving and nurturing Candomblé’s spiritual and cultural traditions.

Beyond religious structure, rituals, and cultural contributions, Candomblé Ketu has been instrumental in promoting social cohesion and resilience within Afro-Brazilian communities. Its emphasis on community, spirituality, and ancestral reverence has provided a foundation for collective strength and cultural pride.

As Brazil continues to evolve, the enduring legacy of Candomblé Ketu stands as a testament to the resilience of African-descended peoples in Brazil, highlighting the importance of cultural preservation and the celebration of diversity in shaping the nation’s identity.